A Brief Introduction

A foundational analysis of

truth vs. Truth

Published on October 1, 2020

by Willie Mc Loud & John Pretorius

“I wish it need not have happened in my time,” said Frodo. “So do I,” said Gandalf, “and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.” J.R.R. Tolkien

“If the foundations are destroyed, what can the righteous do?” Psalm 11:3

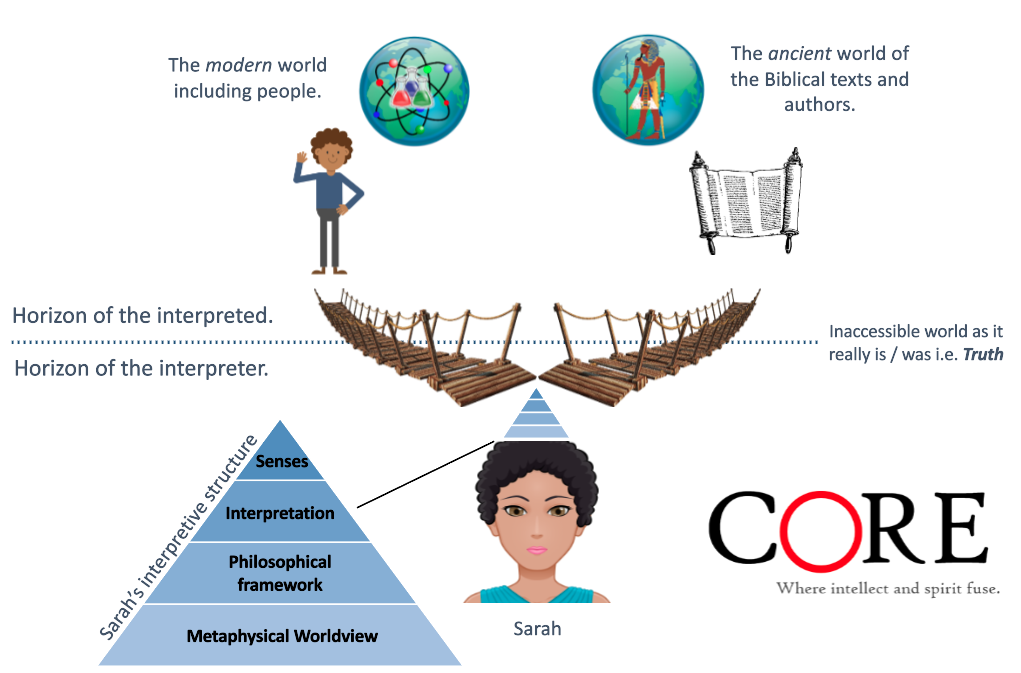

Fig. 1. A diagrammatical portrayal of the deep underlying foundational structures of the human interpretive structure grounding our understanding of the world (the various levels below

the red line agree with the main areas of interest studied and explored on this website).

This means that it is extremely important to have a good understanding of what interpretation entails. To obtain a better understanding of this process of interpretation, to engage with the problem of truth versus Truth, we need to focus on the basic elements underlying the process through which we form our view about Truth, namely what it means to interpret. Accordingly, we also need to be able to distinguish between sound and poor ways of interpreting. The field of studying interpretation is called hermeneutics and we can thus distinguish between sound and poor hermeneutics. Intelligent people often use poor hermeneutics in their interaction with the world for the simple reason that they had been taught this at some academic institution where it has become the foundation of their paradigmatic approach to life without them really understanding and evaluating the soundness of this philosophical approach.

For purposes of this essay (and in general at CoreIdeas) we use the work of the great philosopher of hermeneutics, Hans-Georg Gadamer, to produce a simple model explaining interpretation. This model captures the difference between the interpreter (the person who interprets, their background, worldview and so forth) and the interpreted (all the things that we interpret) and how it all comes together. As such, we must distinguish between 1) our perceptive side, called our “horizon”, on the one hand, and 2) the things we are engaging with in interpretation, which may be the world around us or texts like the Bible (in fact, anything that we try to understand), called the “horizon” behind or underlying those things (the world as it really is or the ancient world from which the text originates), on the other. In all interpretation these two horizons meet each other and fuse into our interpretative framework, as is diagrammatically portrayed in figure 1. In this figure, the various levels of the human interpretive framework, shown below the red line, correspond with the main areas of interest studied and explored at CoreIdeas.

All interpretation is about building a bridge between our horizon and the horizon of the things that we are trying to understand, as Gadamer says: “[W]e define the task of hermeneutics as the bridging of personal or historical distance between minds” (Truth and Method, p95; my accentuation). In our engagement with the past, this “bridging” (see figure 2) becomes possible because we belong to a long and continuous tradition of interpreting the past, a tradition going back to the past itself.

Fig. 2. Textual hermeneutics involves building a hermeneutical bridge

between our modern world and the ancient world.

When we understand the basic elements of all understanding or interpretation, it will help us enormously in our general engagement with the world and with others, bringing that which is hidden deep down as unconscious processes to our awareness, enabling us to examine them more closely and carefully. Our conceptual structure (i.e. all our concepts woven together as a whole) built upon our metaphysical worldview is like an iceberg with large parts under the water, beyond direct view or awareness, without us being consciously aware of it (see figure 1). Let’s then take a look at a short outline of this process of interpretation:

1) Our own horizon. At the basis of all our understanding of things is our metaphysical view of the world, which has been formed over a prolonged period of time through the process of interpretation and might have involved both sound and poor ways of interpreting things. We are usually aware of our general worldview, i.e. whether we are Christians, atheists, agnostics and so forth, although there are people who have not yet formed a final opinion in this regard.

However, what is for the most part unknown to most people, is the basic philosophical framework they use to engage with the world, the most basic philosophical point of departure which might be modernist, postmodernist or something in between. Modernism tends towards an extreme positive belief in obtaining Truth whereas postmodernism harbours extreme doubts and scepticism about obtaining the truth about Truth. Other philosophical frameworks like philosophical hermeneutics have a more balanced and nuanced view about obtaining the truth about Truth. These philosophical frameworks underlying our thought processes are portrayed on the second level of the diagram in figure 1. Most people are not even aware that they use one of these frameworks or some combinations thereof, sometimes even switching and jumping from one to another when engaging with different contexts of life.

Also underlying our interpretative structure is the way we understand the world around us, using our scientific understanding of things to interpret the world (level five in figure 1). When we read an ancient text like the Bible, most people harbour some idea about the ancient world and the worldview of those people, something which helps us to gain a better understanding of the things spoken of and which may be very foreign to us (level four in figure 1). And when we really engage in detail with ancient texts like the Bible, we might also form ideas about the way that such texts came into being and the possible sources used in writing them (level three in figure 1). It is only on the next level, above the red line in our diagram, where we engage with particular things or topics in our world (in science, for example) and texts like the Bible in our understanding of things and passages in it.

2) The horizon of things. In general, this is the world with which we engage. This horizon includes all our interaction with the world, with other people and with texts like the Bible. Although we may hold the Biblical text in our hands, we can never access this text without interpreting it. Our understanding of the Biblical stories and message – as presented by the Church of Jesus Christ – are based on a long tradition of interpreting the Bible (the third, fourth and fifth levels of the diagram in figure 1). The many different denominations existing today testify to the very fact of interpretation even though all Christians can agree on certain core Biblical truths which we all believe to be Truth.

When reading an ancient text like the Bible, we immediately come into interaction with the ancient world in which the authors thereof once lived insofar as it underlies their way of thinking and writing and therefore being present in the text (the fourth level of the diagram in figure 1). Christians are often not even aware of this and project their current scientific understanding of things onto the text as if those people had a similar way of understanding the world, which could obviously not have been the case. Once we obtain some understanding of the ancient worldview of those people, we can gain a better understanding of their writings, of passages in a book like the Bible.

In as far as the world itself is concerned, we have no other way to access it except through our human senses, and by extension through our scientific and other tools and aids. All scientific experiments function within this empirical limitation; it can never go beyond that which is accessible to our senses in our material space-time world. All empirical data belongs to our material world and insofar as our world has non-material aspects embedded in nature itself (the quantum realm and so forth), we can only access that indirectly (see other essays from CoreIdeas for more detailed discussions of this topic) except insofar as we believe that we as Christians interact with the unseen spiritual world on a spiritual level.

In as far as other people are concerned, we interact with them through observing, listening and speaking. We interpret what they say and do, their words and their actions. Nobody has access to another person’s deepest inner being, feelings and thoughts, except within the framework where we interact with them through our senses and interpret them through this lens. In fact, we can take dialogue as an excellent metaphor for interpretation. In the same way that effective dialogue involves really listening to and engaging with the speaker, sound hermeneutics involve respect and openness to the voices and traditions represented in the texts we are reading.

Fig. 3. The two horizons that meet each other in interpretation (the interpretive structure of the interpreter is shown at the bottom whereas that of the other person or ancient author with whom the interpreter engages is shown on top).

Interpretation thus occurs when these two horizons (1 and 2) come together, when they fuse so to say (as is portrayed in figure 1). Insofar as truth is agreement with reality or with what really happened in the case of past events, we arrive at truth when we have a good understanding of our own humanity and individuality (our own way of thinking about the world) as well as of the world, present or past, that we are engaging with. This enables us to come as close as possible to the Truth, to construe well-informed narratives corresponding with the truth. If we have used and developed poor habits of interpretation, based on inferior philosophical frameworks, we will construe inaccurate and false narratives which do not agree with the truth and arrive at misguided and wrong conclusions, forming an inferior metaphysical worldview. It is therefore extremely important to gain a good understanding of all these things.

The single most important problem with interpretation is that people in some way use philosophical frameworks of interpretation based on poor hermeneutics. This means that informed Christians, apologists and Christian leaders must engage effectively with this foundational issue. We should not simply reject a philosophical framework like postmodernism; we also need to understand why both modernism and postmodernism have fatal flaws. It is crucial for us to have a good understanding of the philosophical framework we are consciously or unconsciously using in our interaction with the world, other people and the Biblical text. The most important philosophical frameworks used by people in their interpretation of things are modernism, postmodernism, philosophical hermeneutics (of Hans-Georg Gadamer and Paul Ricoeur), critical realism (of NT Wright and others) and Thomism (of Thomas Aquinas).

We need to understand how these basic philosophical frameworks determine our manner of interpreting the world around us or texts like the Bible. The following question need to be asked: What is the outcome of using each of the above philosophical frameworks? When we, for example, use a modernist framework, believing that we can obtain some kind of objective view of the world through science, we will most likely have a view of the world based on scientism, a view typically found among atheists. If we use a postmodernist framework, we will most likely have a pluralist view, accepting that truth is relative and that nobody can have any claim on the Truth whatsoever. If we, however, reject all forms of relativism (as most Christians do) and have a view agreeing with philosophical hermeneutics (like that of Gadamer), we will most likely accept that even though none has access to the Truth (except on a spiritual or belief level), we can nonetheless form better interpretations based on sound hermeneutics.

Clearly, the million dollar question is: What constitutes “better” interpretations? This is the single most important question that we can ask in hermeneutics. And there is, in fact, a remarkably concise answer to this question, namely that all sound interpretations are able to eliminate real contradictions. There may be a contradiction between our interpretation of reality and what is known about reality or our interpretation may simply not be able to account for inconsistencies and contradictions in our understanding of things. Then it is not a sound interpretation and the narrative or story based on it is not a good one. In fact, in that case it is most likely false or wrong. It is simply not true and does not agree with true reality. All sound interpretations have great explanatory power!

In an effort to throw more light on the issue at hand, we can use the operations of the criminal justice system as an example. In all criminal cases various narratives are presented to the judge (or jury), usually one presented by the defense and one by the prosecutor. The main purpose of court procedure is to establish which narrative is true or at least the most truthful. Now, when listening to witnesses one may find that there are various possible narratives which might be true. This follows from the simple fact that the court often has restricted data in the form of witness testimony or forensic evidence available to it (just like we in general have restricted access to Truth). The main principle used to distinguish between truth and lies is that of non-contradiction. The truth will be in line with the data before the court; all lies will contradict those facts. This principle is undermined when the perceived contradictions are not real due to limited available data or differences in witness testimonies. Sometimes the perceived correspondences may also not be real due to shortcomings in expert witness testimony. This can result in false convictions. Similarly, our greatest enemy in an honest pursuit to form sound interpretations is perceived but false contradictions or perceived but false correspondences.

To conclude our introduction, we can simply note that at CoreIdeas we will be engaging these foundational issues in future essays and articles. We will try our level best to present a nuanced and relevant perspective on core Christian beliefs, provide sensible interpretations of difficult and disputed Biblical passages and the relevant issues of our time. Our aim is to strengthen our Christian foundations and enable Christian leaders and laymen alike to not only make sense of a fast changing world but also to effectively engage with others in the market place of ideas. We will provide tools that will assist Christians in their engagement with others in our goal to reach the world for Jesus Christ.

Willie Mc Loud is an independent South African scholar with a wide field of interest spanning ancient Middle Eastern studies, Kantian philosophy and philosophy of science. He has got a PhD in Nuclear Physics (Nuclear Fusion), a MSc in Physics, a MA in Philosophy of Science, an Honours degree in Philosophical Hermeneutics and an MBL.

John Pretorius is moved by reading, listening to podcasts and seminal discussions including biographies of inspirational people, philosophy, science, technology, psychology, consciousness, theology, mythology, basically any classification of ideas that try to make sense of our reality and truth.